|

|

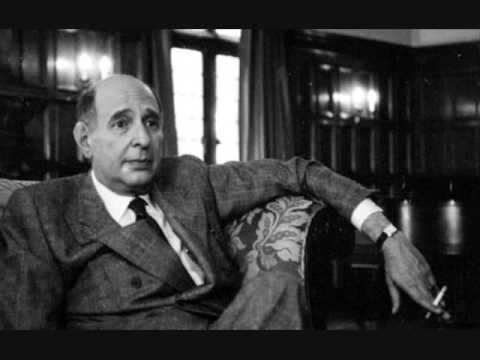

Dweezil Senior vs. Bloom Unit {April 13, 2011 , 7:25 PM} The man that hath no music in himself, Nor is not mov'd with concord of sweet sounds, Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils; The motions of his spirit are dull as night, And his affections dark as Erebus: Let no such man be trusted.—Mark the music. ~Lorenzo, The Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene I In a televised defense of his 1987 treatise on education, The Closing of the American Mind, Allan Bloom felt pressured enough to declare, "I am not a snob!" One of the chapters of the book that had earned him charges of stuffy obscurantism was his critique of popular music; Bloom was a committed classicist and held the position that pop music stunts intellectual and emotional growth, satisfying the human soul about as much as Pot Noodle satisfies the appetite. Jagger, Lennon and Prince provide “premature ecstasy” and therefore destroy the imagination. In line with the book's overarching thesis, Bloom decided that the decline of music as a society’s spiritual and cultural vocabulary has contributed to the strangling of American liberal education. Calling upon the Greeks for support, Bloom asserts that music in its essence is barbaric—but whereas classical works fuse music’s raw energy with a higher principle or expression, rock music, in its vulgarity, keeps the minds of our generation primitive, and its hearts empty. This was and remains a serious charge. Anyone doubting the impact of music on the human personality has a bone to pick with Aristotle, Rousseau and Nietzsche: to invite music is to tap into a world of enthusiasm and passion, so the form in which you digest your Corybantic prescription is of the utmost importance. So in 2011, when Gaga still trumps Grieg, I wonder whether it’s worth revisiting Bloom’s ideas about music and the philosophical project. I invite to the table Mr. Frank Zappa. A few months after Bloom released The Closing of the American Mind, Zappa wrote a critique in New Perspectives Quarterly titled, “On Junk Food for the Soul.” Zappa, it should be noted, completely dismisses the metaphysical theories of Nietzsche and Plato, which happen to constitute the thrust of Bloom’s argument. He’s not being fair to Bloom in this regard, but after some cheap shots, F.Z. does actually challenge Bloom on legitimate grounds: he takes issue with the idea that only classical music is in touch with higher ideals that allows it to satisfy coarse passion without succumbing to its excesses. Bach in all his religiosity and Beethoven in his humanity were, at the end of the day, artists getting paid. So basically, the people who are recognized as the geniuses of classical music had hits. And the person who determined whether or not it was a hit was a king, a duke, or the church or whoever paid the bill…The content of what they wrote was to a degree determined by the musical predilections of the guy who was paying the bill.In this way Zappa states a truth that I must agree is completely glossed over by Bloom: all sponsored music is produce. Classical music holds no virtue over contemporary music in this regard, a reality that does a great deal of damage to the notion that concert music’s survival should somehow convince us of a more genuine and successful synthesis of thymos and rationality. It’s actually shortly after this point that Zappa and Bloom converge. Both disdain the music business. Bloom, eager to wipe the smirks off of those raging against the machine, describes it as "perfect capitalism, supplying to demand and helping to create it." Zappa echoes the charge from his own corner: “Record companies have people who claim to be experts on what the public really wants to hear. And they inflict their taste on the people who actually make the music.” Roger Waters, to his horror, might have also found himself in agreement with Bloom, as the latter's argument that entertainment has become the chief end of contemporary society is the main theme of Waters’ (excellent) solo album, Amused to Death. In the title track, Waters writes of an alien anthropologist who discovers the skeletons of our species “grouped ‘round our TV sets,” left only to conclude that we had “amused ourselves to death.” Though he cited Neil Postman as an inspiration for the album, Waters is speaking Bloom’s language throughout. But to reconvene with Zappa I have to part company with Bloom on the matter of classical music’s superiority in form, essence and effect. From a purely technical standpoint, of course concert music (which is still written today, after all) is more involved, complex and, for the composer, difficult to produce. But Bloom is not speaking of musicality or the art of composition so much as he is addressing what the medium of music has to give—once the pomp and permanence of the classics is debunked by Zappa, we face a level playing field. Consult your own hearts, but I know that I catch just as staggering a feeling of sublimity when listening to Waits’ “Grapefruit Moon” as I do when listening to Beethoven’s Sonata No. 23. While Bloom does identify with those who feel connected to contemporary music early in the chapter, it does not undo what eventually turns up as his most embarrassing passage: his haughty insistence that "people of future civilizations will wonder at [the phenomenon of rock music] and find it as incomprehensible as we do the caste system, witch burning, harems, cannibalism and gladiatorial combats." Bloom does not specify whether or not he is talking about the spectacle of American Gladiator or its Mediterranean predecessor, which I believe might have injected some seriousness into this otherwise ludicrous sentence. With that in mind, it is my opinion that in his discussion of the contemporary recoil from Plato and the young generation’s ferocious defense of pop music’s authenticity, Bloom ends up beautifully articulating what philosophy demands of its students: "Yet if a student can—and this is most difficult and unusual—draw back, get a critical distance on what he clings to, come to doubt the ultimate value of what he loves, he has taken the first and most difficult step toward the philosophic conversion. Indignation is the soul's defense against the wound of doubt about its own; it reorders the cosmos to support the justice of its cause. It justifies putting Socrates to death." In drinking the Kool-Aid, one is merely sweetening the hemlock. Labels: Allan Bloom, classical, Closing of the American Mind, education, music, pop, Zappa ---------- Post a Comment ---------- |

|

|